In this post we’ll examine the concept of integrated business optimization. It’s not uncommon for a CEO or business unit leader to think they have their organization optimized, only to find out that is not the case when volatility strikes. Building a culture of optimization, something that goes beyond spreadsheets and planning and gets to the core of your business, is the key to thriving in times of uncertainty.

Simply put, companies that lead their industries are companies that bring together insight, decision, and process to consistently make the most optimum decisions for their business. They centralize key decisions, implement appropriate systems and processes to support timely and accurate information, then incentivize and empower their teams to leverage these tools to make the best decisions for the business.

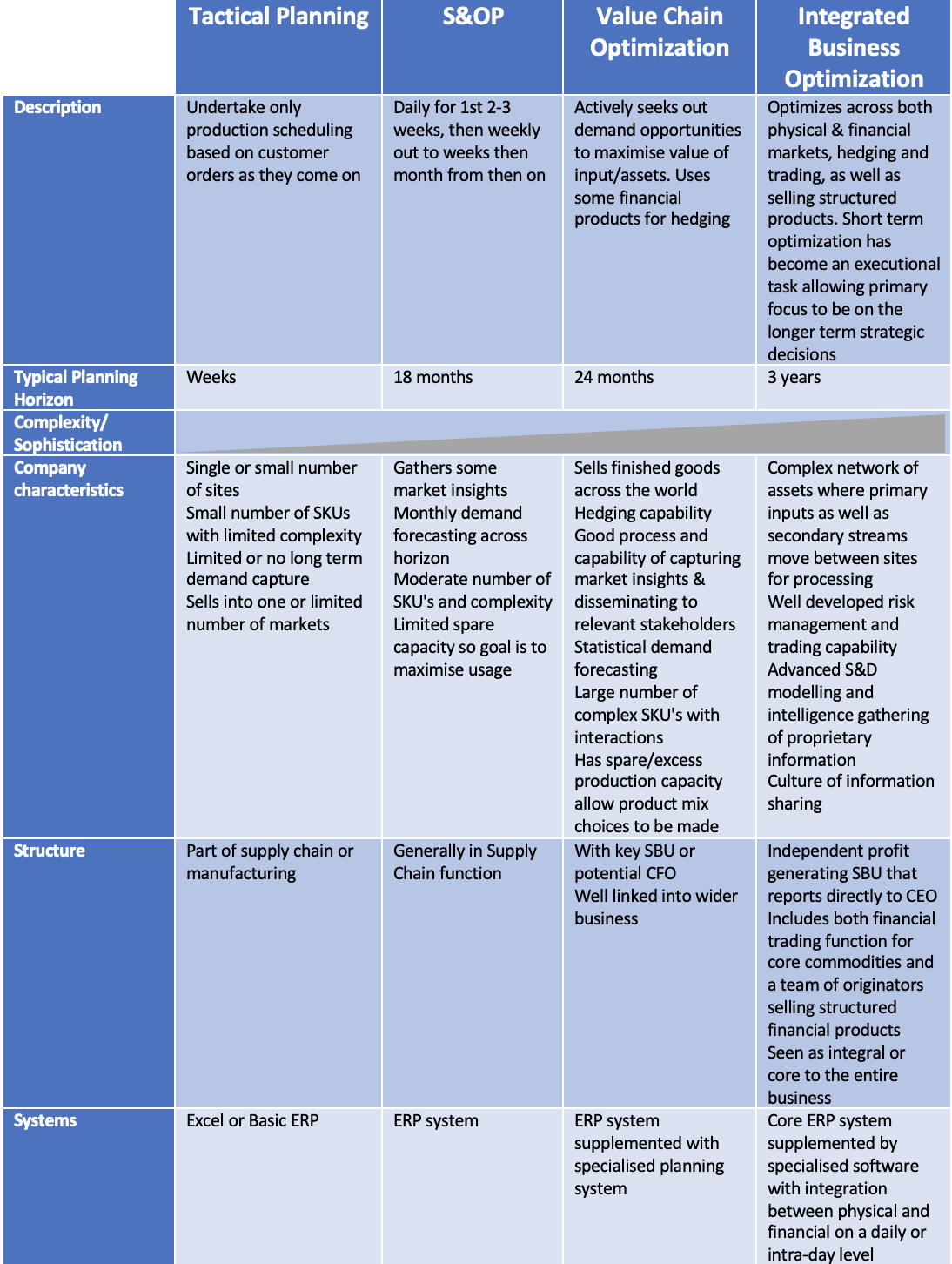

The Four Stages of Optimization Activity: Tactical Planning, S&OP, Value Chain Optimization, Integrated Business Optimization

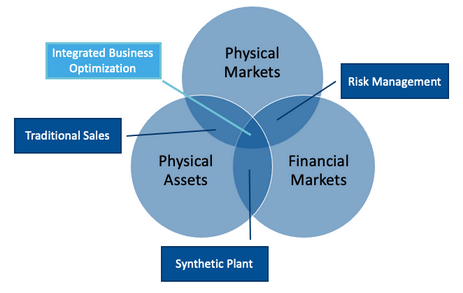

Expanding further, integrated business optimization (IBO) comes at the intersection of optimizing across your production assets, the physical market, and the financial market (as shown in diagram 1). Making decisions across these areas increases complexity and creates more options and choices. This means greater flexibility and profit opportunity, as well as increased offerings for customers. The business model IBO is common in complex agricultural commodities, as well as some non agricultural industries such as the electricity industry, where it is an important source of value and strategic advantage to those who get it right.

Industry Characteristics

Organizations that want to reach the more advanced levels of planning and optimization will need to master certain industry and player characteristics. Typically these include some or all of the following:

- Large overall market size which is in the USD $10’s-$100’s billions

- Significant price volatility in the underlying commodity prices on either the input or output (or both). Price volatility is what creates the biggest opportunity and reason for optimization, as profitability will change depending on what products you choose to make.

- Industry consolidation meaning some large market players on both the production side and the end user side. Scale is required in order to be able to afford to invest in the capability for advanced planning and optimization

- Liquid (or developing) financial markets on which to hedge/trade – these provide an important option to manage risk and seek profit

- Product internationally traded – or, to put it another way, product not solely produced and consumed within the same market

- Raw input has inherent optionality – it can either be broken into multiple different products (disassembled) or can be made in a number of different ways such that the raw material enables optionality, choice, and flexibility, providing scope for optimization

Core Competencies

Core organizational competencies you will need to develop are outlined in diagram 2, then expanded upon in the following sections.

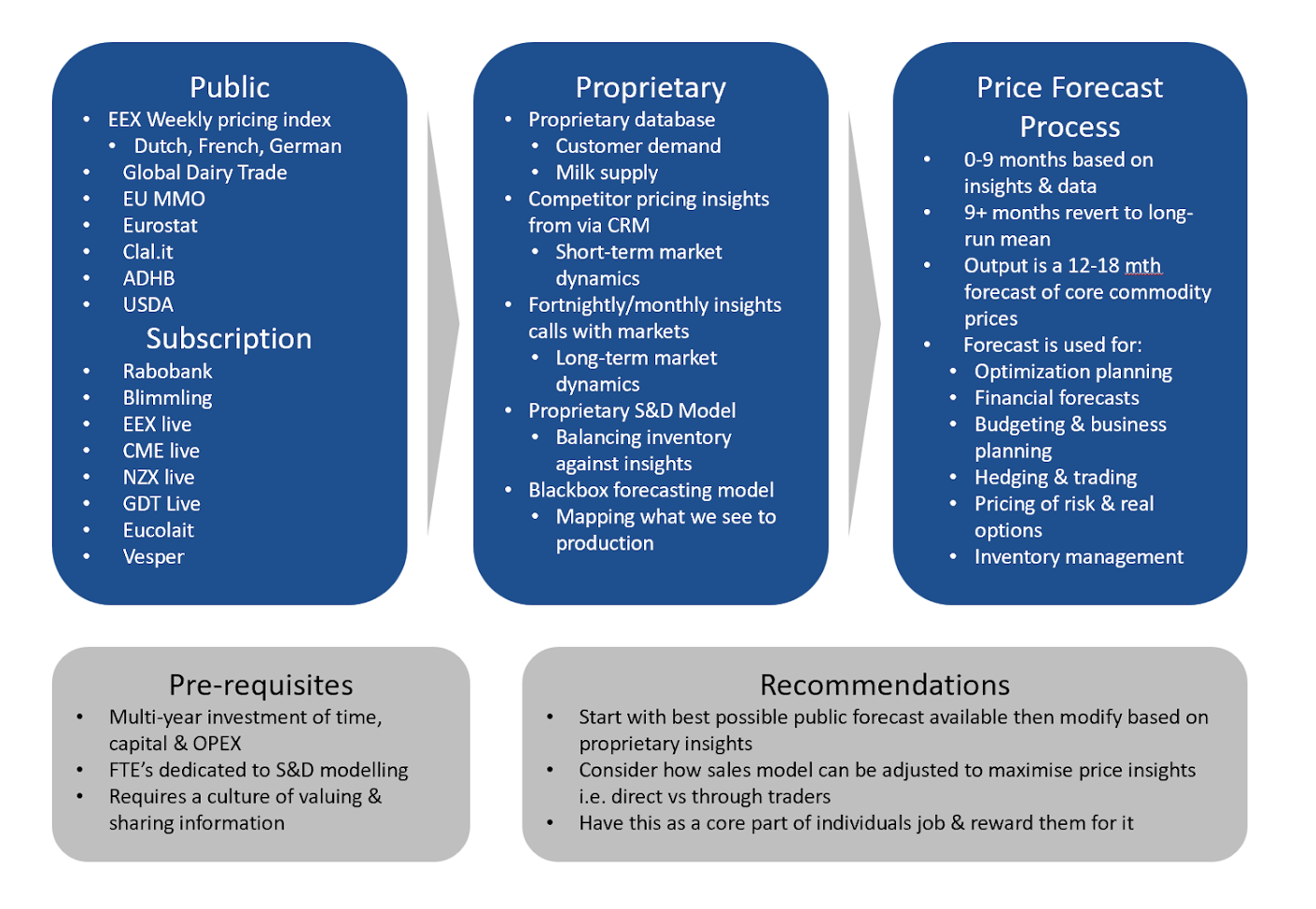

Developing Proprietary Insights and Supply & Demand Modeling

Having accurate and timely information available to you is the basis of good decision making. Large organizations have so much information that it’s often difficult to sift through it all to determine where to focus. A second challenge is distilling all this information into actionable insights on which value accretive decisions can be made. I like to think of it as deciding between what is interesting vs what is important. Proprietary insights refers to information that is unique to your organization or a small group of organizations. When this is information that can drive additional profit it is clearly valuable and important.

Examples of proprietary information include:

- hearing that competitors are willing to sell at prices lower than the current market indicating they have high stocks

- learning there is an outbreak of foot and mouth disease in China that might impact production

- finding that customers warehouses are overflowing with stock indicating that consumer demand is low and they may hold off buying for sometime

In order to gather this information and turn it into actionable insights you need a process and tools. You need to identify what type of information you’re after and communicate this across the organization. Offer a way for people to provide this information into a central team that can then make decisions based on it. It also requires a culture of people who are willing to share and recognized for sharing this information.

An outline of information sources and a process to build a pricing forecast is outlined in diagram 3 below:

A key reinforcing mechanism to make this a sustainable on-going process is that information is collected centrally, insights are generated from this, then the stakeholders share this information back out to the network of suppliers and contributors. This helps them see the value in providing collaborative information and continue to participate.

Innovative examples of proprietary insight gathering I have seen include:

- An Australian-headquartered global mining company that would have people sitting outside key steel producers in China counting truck movements in and out. This was in order to get an accurate view of output and therefore activity and demand instead of relying on delayed and often inaccurate government reports

- A global grain company that would utilize its grain procurement staff during the growing season to gather crop information. While their main job was to purchase grain from growers during the rest of the year they would regularly visit growers and make an assessment of their acreage, crop and weather conditions. But what made their approach innovative was their systematic method of capturing and then utilizing this information to build a supply model at each country/region level. That was then fed centrally into their Swiss based trading function. By doing this and combining it with their demand model one year they were able to identify a significant shortfall due to a poor crop coming out of Australia. They positioned themselves in both the physical and financial grain markets to take advantage of this and made a profit in the high tens of millions that year.

- Competitor price quotes that customers reference in negotiations are entered into the CRM system via an easy to use app-based interface. Price, incoterms, delivery point, product type, quote and delivery date, supplier, etc. are all captured immediately. This was then utilized centrally to work back to a common FAS basis and reported in via a graphical interface against current futures and internal price forecast and current offers to show a pricing distribution.

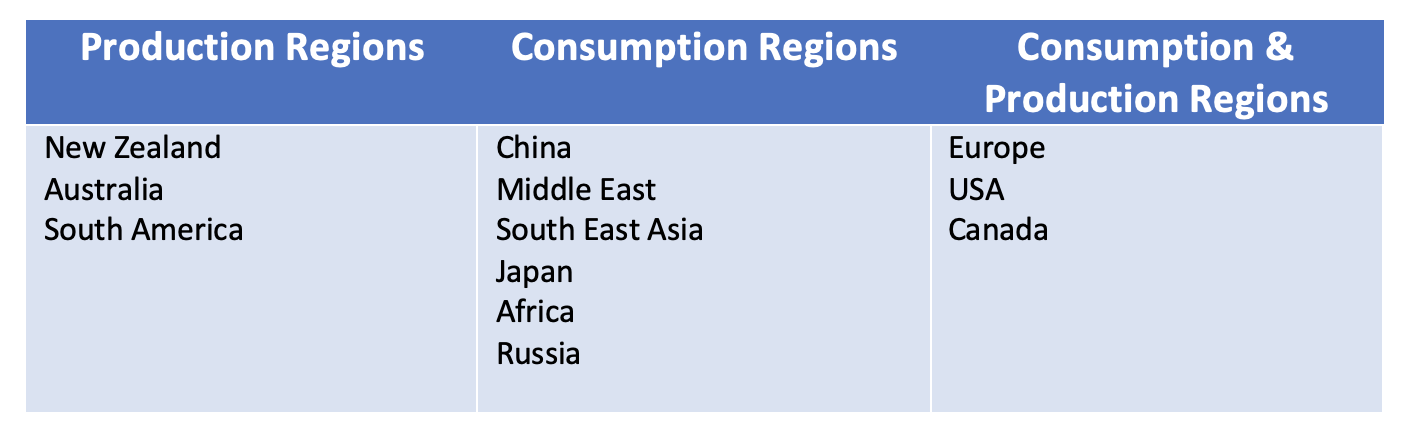

To build a supply and demand model you essentially need to produce a mass balance for each of the key regions that produce and consume dairy and then sum these together. For dairy these regions are shown in table 2 below:

A high-level view of a country-level mass balance equation is below in table 3:

Quantifying and managing price risk

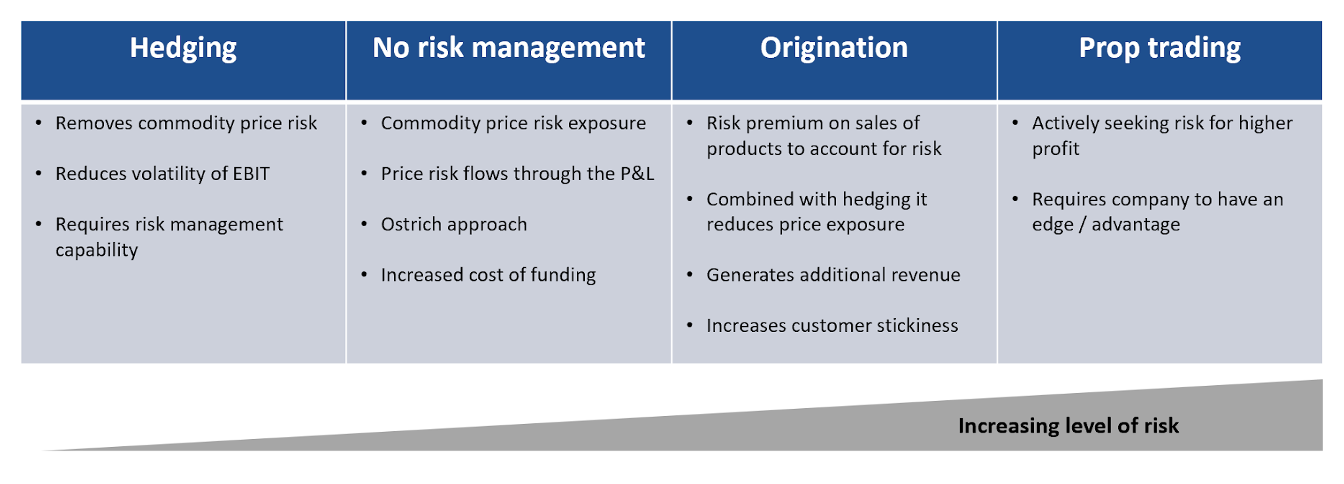

Optimizing across both physical and financial markets while increasing the profit potential of your optimization comes with additional risk. It is critical that you establish a robust risk management process to support this with appropriate controls and governance. My personal view around risk is that doing nothing is actually riskier than hedging your price exposures as outlined in diagram 4, with origination and then prop trading as the riskiest options.

The tried and true process for managing risk involves four basic steps as outlined in diagram 5. The processes must be clear, understood, and adhered to as otherwise this is where many firms fail and the stories of rogue traders building up huge loss-making position originate.

The key steps for managing risk are:

- Identify what your risks are and boil these down to the key pricing exposures and relationships.

- Assess the risks you have identified. You need to determine how material they are and if they warrant the focus and effort to manage them.

- Manage the risk. This means taking steps to control or mitigate the risks you have identified and assessed.

- Lastly, and probably most important, is to then monitor and report on the mitigations you have taken. Are the mitigation steps having the desired effect? Are you staying within the bounds of the policy/strategy? These are key questions to ask.

Entrepreneurial mindset and OK to fail culture

Optimizing across all the key value drivers of a business is complex and challenging – that is why not all business are able to reach this advanced state of optimization. It’s important to realize that you are not always going to get every last decision right. I find it useful to think of it like a portfolio of investments, where the investments are the decisions that you make. Just like a portfolio of investments not all of them are going to increase in value. Some will increase a lot, some will only increase slightly (or not at all) and some will fall in value. The important thing is that in aggregate the portfolio increases in value. The different value decisions you make in optimizing your business are similar. I can tell you now you won’t always get it right and in isolation some will “lose” money. That’s why it is important to accept the mindset that it’s “OK to fail.” Stifle the entrepreneurial mindset by not accepting failure will result in people avoiding decisions, which could lead to failure. This will then result in an aversion to action and value creating decisions will be missed.[1] [2]

Long term vision/thinking

Building the capability that is described in this document is hard, it takes time, and it takes commitment. It needs the support of the senior executive team, including the CEO. A clear vision and long term thinking/commitment is required. In some cases it might take 5+ years, depending on your starting point in terms of maturity. A well articulated vision of where the organization wants to get to is needed, backed up with a good strategy that lays out key milestones and targets. This needs updating at least every two years, and you should consider engaging consultants with relevant experience to help with this.

Sources of value

In my experience the sources of value in order of magnitude from greatest to smallest are as follows:

- Product Mix Optimization

- Origination

- View-Based Hedging

- Geographic Arbitrage

- Proprietary Trading

Product mix optimization

For a large manufacturing business the most value comes from optimizing what mix of products you make and who/where you sell them to. Getting this right should always be your first priority as this is your core business. You have a large asset base and this is about selecting the most profitable demand opportunities to determine exactly what products you should manufacture that maximizes the contribution margin of your assets. This is on of several areas where Austin Data Labs’ scAIcloud® platform can help.

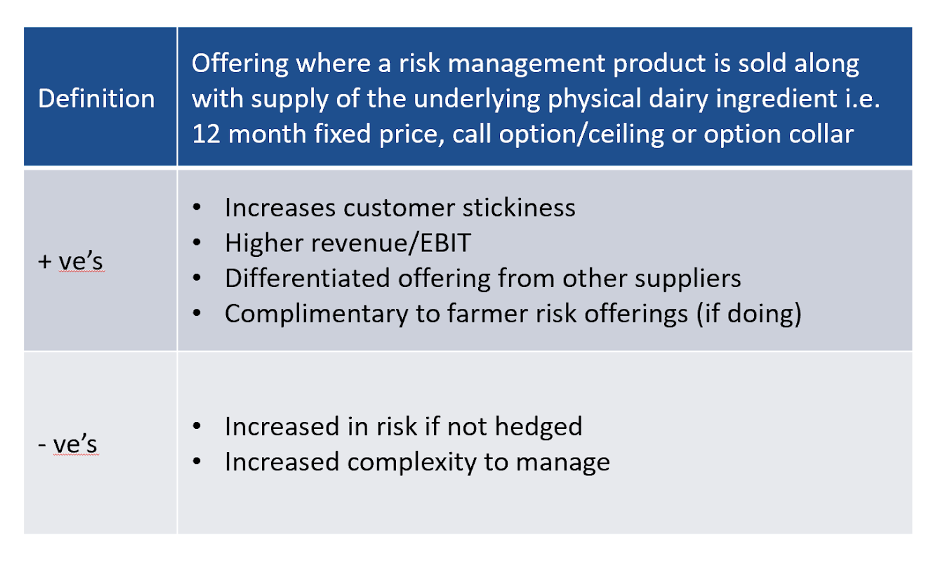

Origination or Structured Products

The term origination comes from the idea that you are actively going out and originating risk because you believe you have the ability to manage it and can increase your profit profile as a result. You do this via what is called structured products where a risk management tool is sold bundled together with underlying physical supply. Table 4 has more detail on this.

It’s important to realize you won’t always get it right so having a portfolio of products and customers then timing each of these goal is important. It means you will have some that will “lose” money while others will “win” but in aggregate the over result is positive if you are pricing the risk properly. On top of this you will hedge some of these sales products by using either financial markets where you take an opposing position to lock in a margin or you offer risk management on the buy side to your suppliers where you lock in your purchase price and their sales price.

View based hedging

Some would call this speculation instead of hedging – the term we often used in jest was “hedge-ulation”. What ever you call it there is value to be had from choosing how you position your physical portfolio based on your view of the market. I am not advocating you do this wholesale and across all exposures. For instance, having a formulaic approach to hedging your currency exposures to provide certainty and remove risk is often the best policy. To use an analogy: if you are buying a home you will change the timing based on what you believe is going to happen to housing prices – if you expect them to keep rising you will buy sooner vs if an economic downturn is coming, interest rates are high, and you expect housing prices to fall then you might choose to wait. When I unexpectedly ended up with 20k MT of product I wasn’t expecting in what I believed was a falling market I chose to sell it quickly before prices declined. I essentially sold around USD $40 million in product in the space of a week and a half which I would have usually sold over the space of say 3 months. My view turned out to be correct and compared to selling it more slowly I estimate I made an extra USD $2-3 million for the business – that is an extra 5-7% return on top line revenue and fell straight through to the bottom line.

Geographic Arbitrage

Geographic arbitrage is where you identify a mis-pricing between different markets or locations and then seek to exploit that. The first point I would make about this is that it is always harder and more complicated than you first expect to execute on these opportunities but that difficulty does make it worth pursuing. Examples of where I have seen this work well is when the commodity ingredient is going into a blended end product like processed cheese or chocolate where the ingredient is being used for composition or functional reasons but not flavor. For many years the USA was a key market for this, as when the USA price diverged from the international price by more than the tariff required to get the product into the USA. Then it made sense to execute this arbitrage. An additional benefit with the USA was that the sales price could be locked in by hedging on the CME.

Proprietary Trading

The key reason I advocate for prop trading is that it means your traders are in the market and it keeps them sharp. Ultimately, you get better execution on your hedging transactions. Prop trading as a source of value itself can be as big or little as you like, but you need to realize you need to hold risk capital against your trading position in case things go the wrong way for you. In an asset-heavy, capital-intensive business this may not be the best use of the businesses capital resources. The other question you have to ask yourself is “what’s your edge or right to win?” What information or advantage do you have over all the other prop traders?

Organizational decisions

There are key organizational decisions that you need to make in order to be able to successfully implement an IBO model. These are highlighted below and then expanded on in the following sections:

- Centralization of decisions into a single group that is responsible for then driving maximum value through the integrated decisions they make

- Centralization of price risk exposures. Similar to above it needs to be clear that the IBO group is responsible for managing pricing exposure or risk and that it has decision rights over this. Management by committee does not work as quick execution is often required.

- Structuring optionality into the business. This is ultimately about have choices over which you can optimize. If you have no optionality then you cant make different decisions to capture more value.

- Own SBU reporting to CEO – this is important as the IBO group needs to be seen to have the authority to make decisions and carry these out.

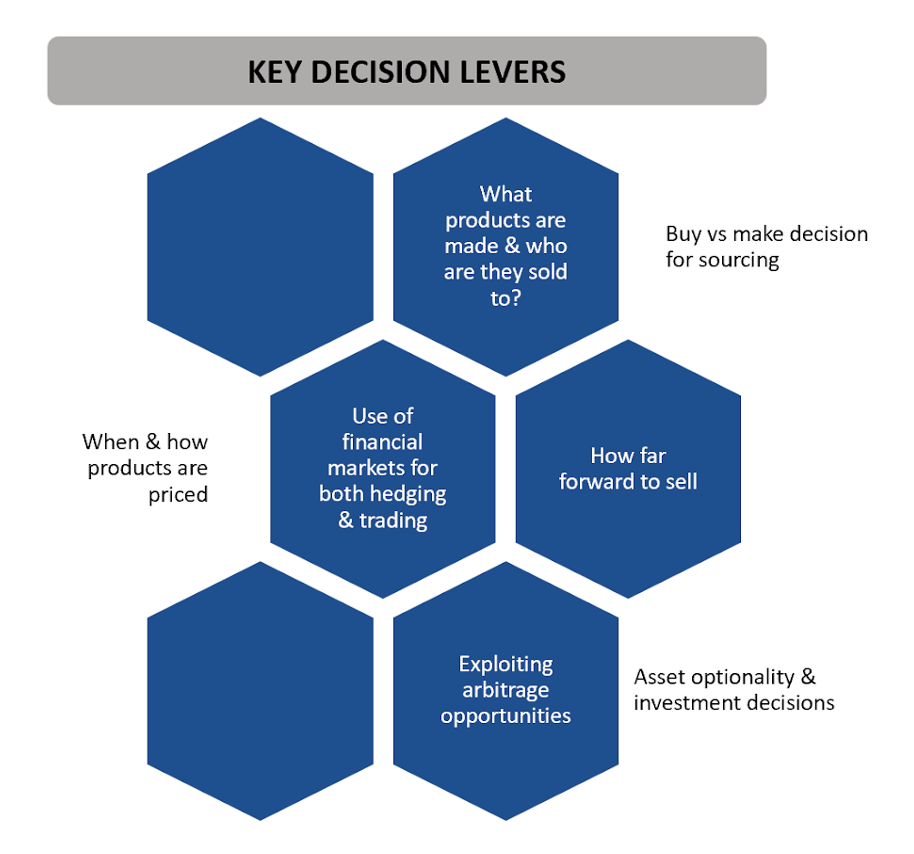

Centralizing decision making

A key concept is the centralization of value-driving decisions into a single function in order to be able to maximize the capture of value. The reason for this is that by enabling a single function to have an end-to-end view across the value levers of the entire organization it then allows them to understand, tweak and adjust these to capture maximum value. The key decision levers are outline in diagram 6 below:

Most of these are self-explanatory, but I will expand briefly on a couple of them to ensure a clearer understanding:

- Buy vs make decision refers to whether you source some of your dairy requirements for CPG products and to supply generic commodity contracts from 3rd party dairy companies or whether you manufacture them internally for use.

- How far forward to sell – this is essentially about controlling the tenor of your sales book. For instance it may be common to sell forward say three months (i.e. the next quarter) but at times you might want to shorten this to two months or expand it out to 4-5 months depending on what is happening with commodity prices i.e. rising vs falling market prices.

Centralization of price risk exposures

To effectively manage all the pricing exposures across a business while minimizing hedging costs and admin it’s important that these are all passed through to the IBO group. The capability to manage commodity price risk effectively is not insignificant so it makes no sense to have multiple functions in different BU’s doing this plus there will be offsetting positions across the BU’s that can be netted off centrally meaning there is no need to go to the financial markets to hedge the exposures. It is also important to do this from a governance and risk perspective as functions that have access to the markets, whether for hedging or trading, need close monitoring and a strong governance process wrapped around them in order to prevent financial market positions exceeding limits and to manage risk capital.

In terms of the pricing exposures it’s not just dairy price risk that should be centralized. Business should look across all commodity pricing risks and bring those in. Examples of these might be:

- Energy exposure from running manufacturing plants

- Coal or Gas exposure from Boilers

- Diesel exposure from Milk Collection Fleet (if done in-house)

- Carbon exposure from the above three

- Sugar exposure if you are using sugar in significant volumes in downstream FMCG BU’s

- Plastics exposure from packaging

- Metals exposure from tin packaging

In doing this it may be necessary to unwind pricing structures from your suppliers of these goods as they may already be hedging it to provide you a fixed price but are likely to be charging a margin for this – there is therefore potential cost savings here on procurement. What you ultimately want is where you are purchasing a good that contains the above inputs you want to have it linked to the underlying market accepted index price plus a margin for processing etc for the supplier.

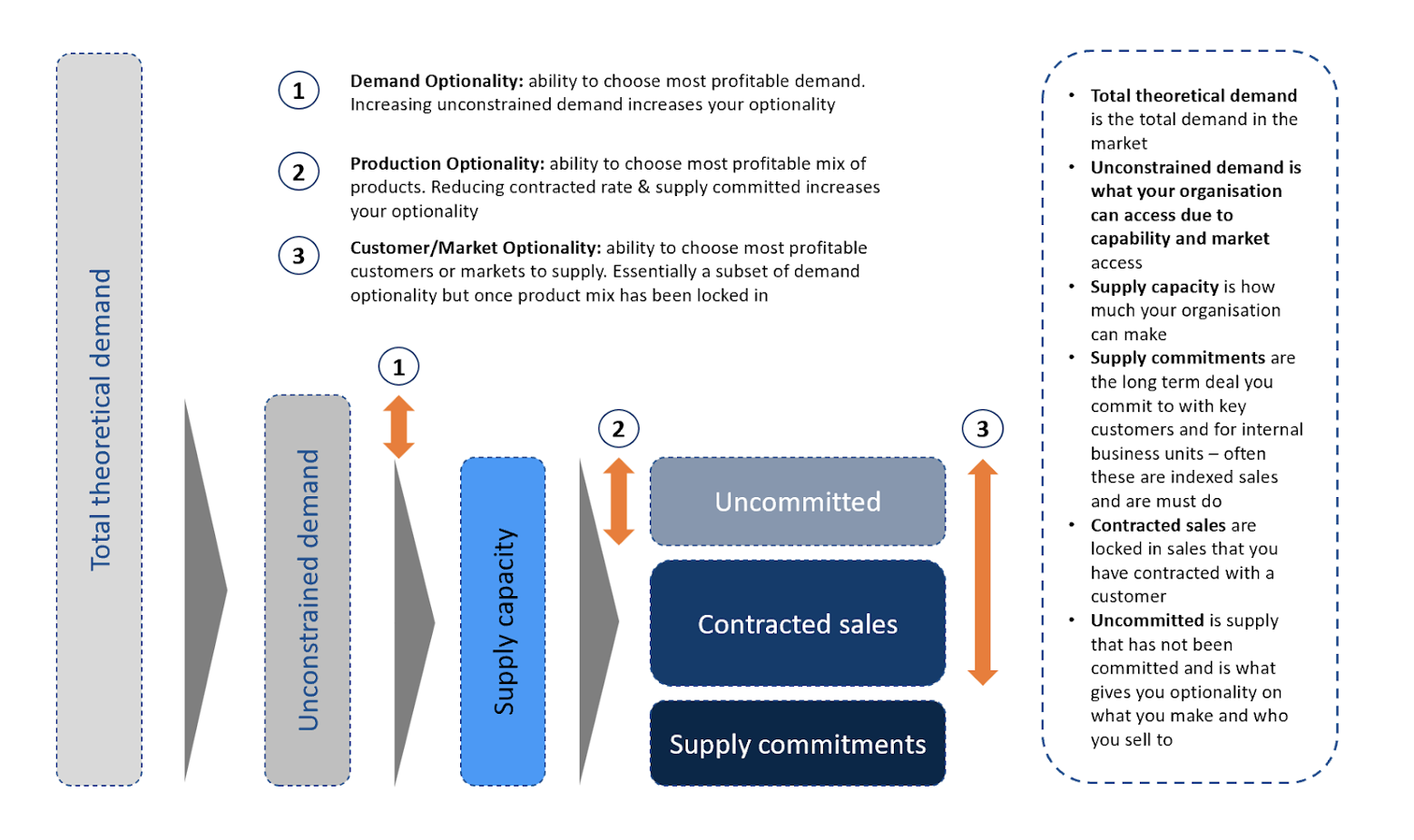

Building optionality

A conscious choice must be made to build optionality or choices into the business. Its also important to remember that optionality generally isn’t free so must have intent of using it as otherwise you are paying for optionality while not getting the value of using it. Think of it like insurance; you pay a premium to get insurance and this gives you optionality. If your house burns down or you crash your car you essentially have a put option to sell your car or house to your insurance company.

Some common ways to build optionality are outlined below:

- Flex in sales and purchasing contracts. This can come in a number of forms; it could be flexibility in the volume that is delivered ie +/- say 5 or 10%; it could be in the origin of the product you supply ie from NZ or Australia; it may be in the specification of product that you supply that gives a wider limit on certain parameters; the options are endless really

- Index pricing is when you link the sales price to a market index and the price varies over the duration of the contract based on the way in which it is linked to the index. For instance it is common for sellers of commodity WMP and SMP to link the price to the average of the C2 price for the month. This has the benefit that the NZX WMP and SMP futures and options contract settle against this mechanism meaning there is no slippage in the hedged price vs the underlying physical sales pricing

- Contract tenor is essentially about how far forward you choose to sell and price your sales book. Are you committing to contracts out one, two, three months or longer for instance say the next six months or a year? This is particularly important when you are offering a fixed price in the contract as it essentially opens both sides up to risk of the price moving.

- Long term supply arrangements (LTSA) are where you enter into a multi-year sales arrangement that commits a volume of particular products to be sold. Commonly there will be an agreed pricing mechanism in the contract such as index pricing. The more LTSA’s you enter into the less product mix flex you will have in your portfolio. While personally I would advocate for some LTSA’s in the sales book (as long as they are indexed priced) I would caution about having too much committed in this manner. IN my view 30-40% in the LTSA space is a good target.

The following diagram illustrates where optionality resides within the allocation of supply against demand.

What I haven’t covered here is developing the capability to be able to price this optionality – look out for a future paper on the value of flex by Robbie Turner

Build and buy recruitment approach

So what is the best way to build the capability and team you will require to execute on this? In my experience a combination of external recruitment for some roles and taking key talent from within and training them is the best overall approach to ensure longterm success. Some of the roles have very specific expertise that are required, would take a long time to develop internally or you need the capability immediately in which case I recommend going external in this case. For other roles where understanding of the business and personal networks are required then it is best to go for internal candidates and then train them in the optimization, planning, risk and trading capabilities that are needed. This dual sourcing strategy has the advantage of getting up to speed in a timely fashion while mitigating the risk that the team is just seen as a bunch of externals and not part of the larger organization team. Another key strategy is bringing people into the team on secondment, for a short term and accessing new graduates into the company which you then expect to move on to bigger and brighter things elsewhere in the company – this has the advantage of “spreading the word” across the organization and helps embed the function.

Education & Change Management

Building a capability towards IBO takes time, is a significant investment in capability and can be a long journey typically taking between 5-10 years or more depending on your starting point. While embarking on this journey it is important to consider how you will manage the change and bring the rest of the business along. Some parts of the organization will see IBO as a threat where decision making and power is being taken away from them. To combat this it is important to explain “the why” this is being done and build trust with the business. Education is a key part of the journey and one thing I would caution against is making the function/process seem like a black box. The business needs to understand what is being done in order to gain trust.

System requirements

At a minimum you would need the following systems with close to real time integration of data in between them:

- An ERP system to act as your system of record

- A planning/optimization system that ideally also includes price optimization

- A risk and trading system including for the booking of deals

- CRM system to gather intelligence and act as the single interface for sales team

A company that excels at integrating optimization and knowledge understands how to bring an entrepreneurial mindset into even the largest organization. This level of optimization is challenging, but developing a culture where knowledge is shared and the mindset that failure is not only acceptable but a necessary part of process development and change management is key to success.

Integrating optimization into the advanced processes referenced in this paper will take time and commitment. The support of the senior executive team and the CEO is essential to success, as well as buy-in from every part of the organization. Clear vision with targets and milestones spanning 5 – 10 years, depending on the company’s level of maturity, will drive success. Updating the vision regularly as new information on the markets you serve develops is required. Engaging a team such as Austin Data Labs to support your optimization and help you manage change within your organization can ensure your success.

Ready to explore how we can help you with your IBO program? Let us know!